Show Word Count

subscribe

Email registration

Thank you for contacting me.

I will get back to you as soon as possible.

Oops, there was an error sending your message.

Please try again later.

Please try again later.

faqs

why should I sub?

In Show Word Count, I use my recent projects to share behind-the-curtain details on a writing life. This includes insights on sourcing, interviewing, writing, pitching, editing, and publishing processes, as well as ideas which couldn’t be explored in the published versions of pieces. If you’re interested in writing, journalism, poetry, memoir, or exploring ideas, this newsletter might be for you!

when do you send it?

New editions of Show Word Count are sent out on the third Monday of every month.

recent word counts

By Aoife Hilton

•

March 17, 2025

Our community is now called Hilley Literary, after two-thirds of us organisers (Bronwyn and I) moved interstate. Drink every time I mention moving. We renamed it because The Braddyton was a space which belonged to the three of us. Its original name came from a combination of ours, and it referenced a physical location: our home. The Braddyton needed its lawn mowed. The Braddyton’s bathroom was upstairs. Guests were invited to a poetry night at The Braddyton. This project began, as I’ve said before, as a backyard gig. The physical space we inhabited informed every one of our events. We had the nexus bedroom. The murder room. The piss-hand zone. The suspicious concrete slab. Until we didn’t. When our events became slightly too ambitious for a backyard, we moved into Can You Keep A Secret in Woolloongabba. And when we wanted to get some writing done, we hosted sprints online. The project began to transcend the place. Then we moved out. Rhys, who so generously mowed the lawn and helped set up the fairy lights for our backyard gigs, is still in Meanjin. But Bronwyn and I are now in New South Wales for her degree. We no longer have the place or all three people. It would have been disingenuous to keep the name. Hilley Literary is a project that still seeks opportunities for writey-writey nerds to share their work, appreciate others’ and set aside the time to hone their craft. Its new name reflects Bronwyn and my continued involvement, and expands its reach beyond a property line. Right now, we have a weekly quiet writing session on Discord . We are still settling in to see what other beautiful things we can conjure. In the meantime, I am reducing the frequency of these newsletters to once a month – on the third Monday of every month. Be in touch soon. Word Count: 328

By Aoife Hilton

•

March 3, 2025

At some point there will be a time when I don’t start a newsletter with ‘I’ve just moved’, but it’s been like three weeks so give me a break. I’ve just moved to the NSW South Coast. It’s taken a toll on my body, as I knew it would. Luckily, I had the foresight and the privilege to take plenty of annual leave at the end of my contract for my previous role in Meanjin – giving me time to set up and find another job. I had been applying since November and getting a bit nervous when I didn’t have another contract signed by the time we were packing up the truck, but in a stroke of good fortune I got a phone call with an offer during the twelve-hour drive down. It meant I had a week of annual leave between arriving in my new home and starting at my new job. And I knew exactly what I wanted to do with it. And I know how this sounds. BREAKING NEWS: Zoomer Last To Discover Normal Work-Life Balance Helps Everything, Including Writing. And yeah that is pretty much it. But I was honestly amazed by what I could achieve while I wasn’t worried about surviving. While I’m not being paid, I’m so caught up in the desperate struggle to get paid that writing creatively goes on the back-burner. And I can see immediately the difference after starting work – by the end of the workday my brain is already tired out, and the best I can do is cobble together another 500 words. During that one week, though, I started on a fiction idea I’ve been mulling over for nearly a year but never getting down. And wrote half of it. I produced more creative work by word count in that week than I have in the previous six months. If you get the chance to take a paid week off work and write, I would highly recommend doing so. How do you harness this extra time, though? There were a few moments during that week when I felt the temptation to sink into my bed and scroll on my phone a bit longer. Part of me itched to check my work email. It can be difficult, even when you’ve taken free time, to appreciate it. If you’re burnt out, it’s hard to be anything but tired and do anything but be tired. I also had house-setting-up things to do and so I structured my writing around that. I would start the day by making a cup of tea and chucking a podcast on, and sorting the house until the episode was over. Then, I told myself, I would write a page. More often than not it turned into two or three pages before I needed to think about what came next. And when I did, I refused to sit there and watch the still screen and think I’m so tired, I can’t do this . Instead, I would chuck a podcast on, get myself a little treat and sort some stuff around the house. It was doing the double-duty of giving me space away from the screen to think about the story’s trajectory in detail. Come back for a page, or three. Repeat. This method saw me through about 2,000 words per day. Maybe something like that would work for you? Now that I’m back at work and groaning in misery at the thought of typing another word after each workday, I am really looking forward to weekends. That’s because every Saturday evening at 6pm-8pm AEST (7pm-9pm AEDT) I’m hosting writing sessions on our literary community Discord . You might know it as The Braddyton, but we’ve renamed it Hilley Literary to reflect our new activities in this new place. I might do a newsletter about that in the future. These sessions are a great excuse to set aside some time for writing. We’re using the pomodoro method (30 minutes of quiet writing, a break, repeat) so we can chat to each other in breaks but also actually get things done. Feel free to drop in at any time during the sessions, and don’t worry about making it to every one – even just the one little visit is great! Word Count: 707

By Aoife Hilton

•

February 17, 2025

Before I left Meanjin, I performed one last set at poets@stones. It included some old favourites and some newbies, including A Galaxy Of . This poem captures an experience seeing glow worms for the first time. It’s probably my best attempt at nature writing to date – and I spent the entire time writing it under the long shadow of climate change. I don’t need to explain climate change to you, but I will offer a definition of nature writing. Noted nature writer David Rains Wallace said in 1984 that works in the genre “are appreciative esthetic responses to a scientific view of nature”, and alongside essays there is “nature fiction, nature poetry, nature reporting, even nature drama, if television documentary narrations are literature”. He called it “revolutionary”. I based my poem on a glow worm experience in Lamington National Park with one of my Americans. Not only did his visit inspire the endeavour (you never really think of exploring your own region by yourself), but the sheen of new-place enthusiasm in his eyes would rub off on yours if you looked long enough. Long after he left, I would drive across the Story Bridge or down a particularly dramatic hill and feel enough to cry. During the visit, I smiled our way up the winding and pot-holed road to Lamington – enjoying mother nature making us work for it. My American came and left in the August heatwave, when temperatures never sank below 25C. We attended a guided tour, a dozen in the group. The guide took us on a short bus ride from the tour centre down to a walking track, where we waddled single-file with red lights in hand. White light would burn the glow worms, so we squinted and huddled away from funnel-web spiders and gympie-gympie. When we arrived at the viewing site – three rows of benches a creek away from a wall of dirt overhung by moss – the water vapour around us had condensed into drops on the tips of our noses. Two kids swung around their red torches until they were wrested away, and the glow worms appeared blue on the wall after thirty seconds of darkness. Our guide relayed glow worm facts to us one at a time in low tones, seconds of silence to let us soak it in. This is one of the only known glow worm sites left in Australia. Other sites have been destroyed by overtourism. Adults are flies which only travel a few metres in their life. Even the red light can hurt them. The next line was not really true. They’re actually yellow, he said. They only look blue to the kids because their eyes are damaged from screen time. To be clear, Australian glow worms are blue. This is a story to scare children off their iPad. But it sparked a kind of grief in me: the rarity of the worms, their decline, that we wouldn’t recognise them as adults, that we maybe don’t recognise them either way. My American challenged me to write about the experience, and I couldn’t help but come back to this sense of loss. That if you think hard enough about any aspect of nature, you get to the part where we’re losing it. Laura Pritchett, a modern nature writer of the American West, says acknowledging climate change is essential to the genre. She wrote in a 2024 piece that the best nature writing centres “the idea that caretaking of the planet is worthy of exploration, the highest of human endeavors, the best survival story of all survival stories … The themes are driven by enormous existential questions not about love or religion or economies, but the fate of life itself.” A work of nature writing can be “celebration or advocacy. Delight or deep ecogrief. Investigative or informative” but the modern nature writing voice is often “stronger, more intense, more laser-focused” on the changing climate than before. “It’s like the gentrified tea parties of yesteryear got taken over by ragers.” Write what you know, I guess. I can’t share the whole poem with you, but here’s a snip of the end: yellow is my favourite colour, I tell him. mine too, he says. I have a habit of mourning worlds I’ve never seen. we’re home to the most endangered species on the planet, he says, and we have a habit of measuring our worth by how much we have lost. Word Count: 739

By Aoife Hilton

•

February 3, 2025

I’ve made a big deal these past few weeks about leaving. There was a newsletter on it. There was a farewell poetry event. Right now, I’m in a Canberra hotel room on my little ‘farewell tour’ seeing friends and family before I go. And during this process, a few people have asked: what’s next for The Braddyton? For those who don’t know, The Braddyton is a literary community my housemates and I created in Moorooka, unofficially renaming our house and hosting events in it. As the events grew, we moved some into the Woolloongabba venue Can You Keep A Secret? and online on our Discord server . We started hosting events because we felt Meanjin had lost some of its vital creative spaces in the past few years. This project was aimed at inspiring creators to continue sharing their work while giving organisers time to regroup after some heavy venue losses. And it worked. For those already attending poetry events and looking for more, SpeakEasy Poetry is returning at Echo & Bounce . We are so, so proud. The truth is, we don’t know if we will continue The Braddyton’s in-person events after the move. We’re moving to a small town in New South Wales. Its creatives will likely have vastly different needs to those in Meanjin. In my opinion, the saddest and stupidest thing we could do would be to copy and paste this project in a different place. We would be neglecting local artists’ actual problems by serving our own egos. The Braddyton was made to help, so we need some time to figure out how best we can do that anew. That means we will take a break from running in-person events for a while. However, I previously mentioned our Discord server . This was initially set up to facilitate a month-long writing sprint in November last year. Since some writers found it helpful then, we want to revive it for something more permanent. Beginning the 1st of March, I will be hosting weekly two-hour-long writing sessions on the server from 7-9pm AEDT (6-8pm AEST). That’s every Saturday evening. Feel free to join as much or little as you like – just drop in for one if that suits you best. We also have a text channel for feedback if you’re not free at the allotted time but still want to share. I’ve made a big deal about leaving, but I promise to haunt you. And if you still think of this as another loss, I dare you to do something even better. Word Count: 421

By Aoife Hilton

•

January 6, 2025

Blue Bottle Journal will celebrate its fifth anniversary in June this year. Founding editor Sean West brought the project to life during the lockdowns of mid- 2020 , and has been accepting submissions about every second month since. Here are some of my favourite poems from each year of the journal’s life so far. 2020: House Hunters While house hunting for an upcoming move, I am of course drawn to Rae White comparing me to a lapwing – the desperate search for shelter like the bird’s forage for food. The never-ending nightmare of mowing is too real. And the feather-friend answer to a cat’s “if I fits, I sits”: “if it flat, we nest”. 2021: Life is Occupation This found poem from Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of the Island evokes the tragedy and violence of a society occupied, the pain endured from the sanding down of identity into someone else’s normalcy. Svetlana Sterlin notes the surviving pre-occupation objects are “pretentions sprawling protectively / over no great art” while the subject will “go down to my grave / unwept, unhonoured, and unsung”. 2022: Angourie, NSW. Have I become obsessed with New South Wales-based things since planning to move interstate? Is it my dream to write poems about the ominous quiet of a seaside town? Did I look up Angourie and add it to my visit list after reading? Look. We may never know the answers to these questions. But Emily Bartlett ’s words did something to me, OK? 2023: I am the swarm Nikita Kostaschuk (ink.eyta) has written a few poems about executive dysfunction – ghosts of Meanjin literary events might be familiar with their sisyphean dishes. In I am the swarm , they seem to plead with their housemate to recognise their humanity beyond their ability to provide labour. It’s a worthy addition to the growing canon of their anti-capitalist, ADHD-coded work. 2024: The Pearl as Immune Response As a sapphic, I can’t deny the appeal of heartbreak and the sea. Maddy Dale ’s picture of a heartbroken soul in the shallows satisfies the aesthetic urge. The sea creates wonders and destroys them and doesn’t care either way. After realising you did, too, maybe that’s the best place to let go. 2025: Ceviche The first and only poem yet published by Blue Bottle this year, Ceviche automatically gets the spot. But it deserves it nonetheless. Paris Rosemont ’s biting description underscores the carnal want, neediness of a sexual relationship. Blue Bottle is collaborating with The Braddyton – a literary community project by myself and my housemates – on a poetry event for Saturday, January the 18th from 3pm to 5pm. Join us for an afternoon of curated poetry by Rae White, Maddy Dale, Svetlana Sterlin and Shastra Deo! Word Count: 447

By Aoife Hilton

•

December 23, 2024

Shastra Deo’s second book The Exclusion Zone begins with a dare: turn to page 5. But this isn’t the choose-your-own adventure novel of your grandparents’ childhoods. There are no dice. There is no prose. Sometimes there is not even a choice. UQP published The Exclusion Zone last year, and yes I’m only reviewing it now because Shastra is tragically leaving Australia for the United States and performing in January before she goes. But I would also argue its themes have only snowballed in relevance since its publication. This is a choose-your-own-adventure poetry collection set in an apocalyptic hellscape. Which is certainly a string of words. When it first came out, Shastra appeared at a Brisbane Writers Festival event where she gave some insight as to how she can write poetry into an overall story, let alone many overall storylines with alternate endings. “I’m a fiction writer,” she said at the time. “When I discovered poetry, I thought, ‘Oh, I can write short fiction, but even shorter?’” This attitude towards the form shines in The Exclusion Zone . ‘Aubade’ tells the story of a boy starving. ‘Transcript of a Fight Scene’ is, in fact, a fight scene. But it’s not really prose fiction, that it’s all referring to. Also in that conversation, Shastra assured the audience there was no ‘right way’ to read the book. If you want to read it front to back and ignore the prompts, nothing is stopping you, and you should still have a good experience (a relief to me, a completionist worried about missing out on certain poems should I follow a certain path). She said she wanted it to feel like an open-world video game. This is front-and-centre in The Exclusion Zone , which has a section called ‘The Game Room’ and poems which use controller symbols, language like ‘walkthrough’, structures like flow-charts. Although it doesn’t rely on specific game references, it’s heavily mired in the culture of gaming. When we add that to the full-on sentence from earlier, the genre-mash up seems overwhelming. But from its first page, The Exclusion Zone blends these elements together to create the feeling of being inside the best eerie dystopian RPG. Think: if you could have all the Death Stranding vibes and none of the annoyance of actually playing the game. These are not the relevant-to-2024 themes I was referencing earlier, though. I personally would love to see a suddenly ballooning market for gamer-culture choose-your-own-adventure apocalyptic poetry collections, but The Exclusion Zone remains unique. I was talking about why there’s an apocalypse. The last line from Shastra’s Brisbane Writers Festival chat I’ll recall is an insistence that the poems in this collection are fictional, that she did not recount her own life events and experiences for this book but rather imagined a story where these poems would live. But the story is rooted in reality. While some of it only hints vaguely at a collapse of humanity (like in ‘How Deep’) and some suggests a far-future setting (like ‘Aubade’), many of the poems in this collection directly comment on modern historical events (‘Fukushima Soil’, ‘Things We Inscribed In The Voyager Golden Record’, ‘Undertakers Of The Atom’). Some appear to describe contemporary moments (‘Fishing at Caer a’Muirehen’, ‘Learning A Dead Language’, ‘Shastra Deo’). Even these create a sense of an ending. The inclusion of modern history, contemporary scenery, near-future, indescribable collapse and far-future poetry implies a real opinion if it doesn’t actually tell it to you. When we face seemingly endlessly increasing disaster, tragedy, conflict, death, the core of this collection becomes less and less fictional: We are in the prequel of the apocalypse. We are searching for something. We are waiting for someone to answer. Sometimes there is not a choice. Where will we turn next? Word Count: 653

By Aoife Hilton

•

December 9, 2024

Those who follow The Braddyton literary community might have noticed a distinct lack of events this month. We’re taking a bit of a break from the literary madness following a thoroughly mad November, but we’ll be back in January with a very special poetry event at Can You Keep A Secret. Why is this event so special? Well. We’re leaving. I set up The Braddyton with my housemates Bronwyn and Rhys to serve Magandjin’s literary freaks after some of our key events shut down. SpeakEasy. Gather Round. Lonely’s. Volta. The seeming mass dismantling of this city’s literary community became such a sticking point in conversation that we became annoying at parties. Our friends were exhausted with our complaining. ‘Why don’t you just set one up then?’ So we did. It has been such a magical experience, from making tea and sharing poetry in our backyard to booking a venue for Halloween. An abundance of cheesecakes. Chocolate-chip cookies. Rooibos chai. Fairy lights. Too many cushions. Shouting poetry over road noise. And last month, a near-daily writing challenge on Discord. But Bronwyn has been accepted into a postgraduate program interstate, and we’ve decided it’s time for a life change. Bronwyn and I are heading for the NSW South Coast, and we’re bringing this project with us – whatever it becomes. January’s event is a collaboration with Blue Bottle Journal, involving Sean West, Shastra Deo and other fantastic writers. Because we’re also seeing Shastra off before she moves to the US. It’s just one big farewell party, y’all. Look out for more info coming soon. As we prepare to say our goodbyes, I’d like to invite you to become the annoying person at parties. We set this up because we care about our literary community here. What are you willing to do for it? Word Count: 300

By Aoife Hilton

•

November 25, 2024

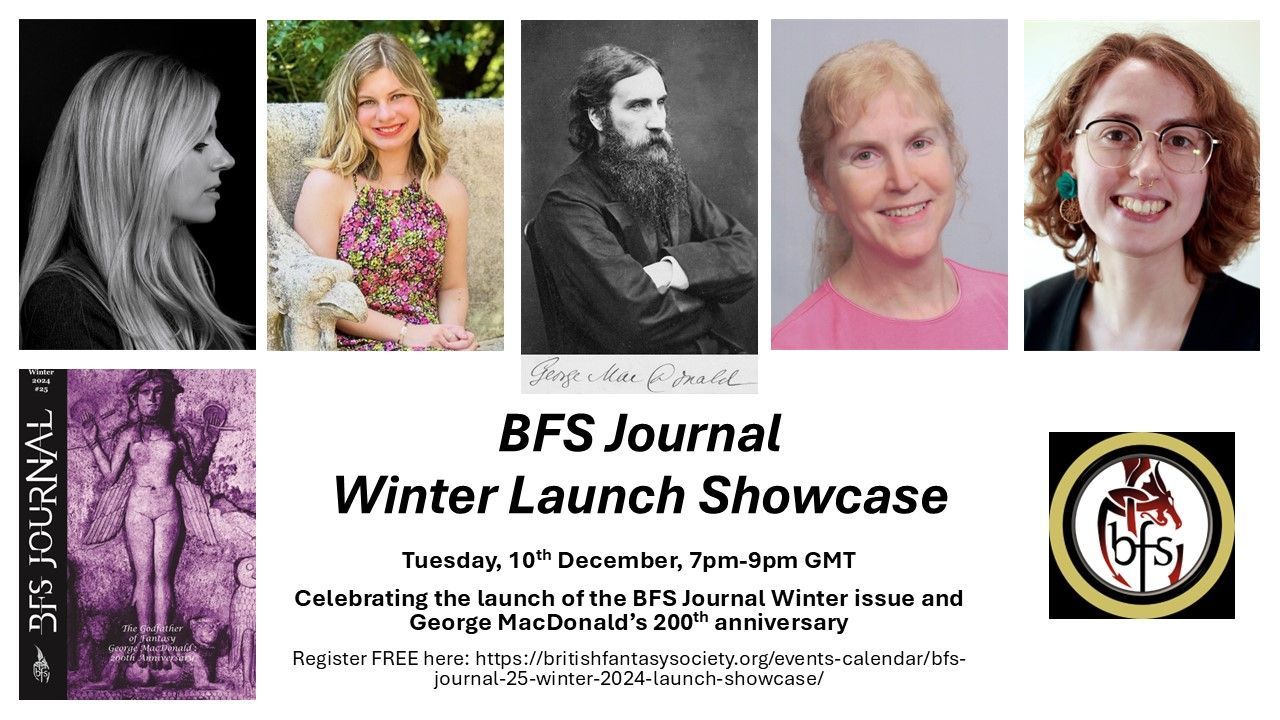

My academic piece 'A New Definition For Literary Fantasy' will be published in the winter edition of the British Fantasy Society journal , out on December 10. This is a literature review looking at the ways in which academics and publishers have used the term ‘literary fantasy’ when writing, reading, studying, and marketing different works. The subtitle on this piece is ‘Looking beyond publishing elitism’. And this is for a reason. I found that academics and publishers have often used the term ‘literary fantasy’ to mean ‘good fantasy’ – couching personal preference in the appearance of ‘literary’ legitimacy, and falsely justifying elitism. But I also found that the term is not actually well-known at all outside this circle. I surveyed a group of readers at UQ and online, and asked what it meant to them. Some used the term to mean ‘fantasy fiction’ – deeming the ‘literary’ not as a genre marker but simply a signpost that we were in fact talking about books. Literary fantasy is a hybrid genre between literary fiction and fantasy fiction. You might have seen hybrid genres before. Romantasy, or hybrid romance/fantasy, is one of the most popular. Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell is a historic fantasy. Frankenstein is gothic science fiction. But there’s trouble in hybridising with the literary fiction genre. Namely, no one seems to agree on exactly what ‘literary’ means. Oh, you’ve seen it around. UQP is a ‘literary’ publisher – never publishing genre fiction except for all the times they do. The classics all seem to be ‘literary’. And contemporary ‘literary’ isn’t too hard to spot. Think Sally Rooney. Think The Lovely Bones . There is something identifiable about it, even if it’s hard to pin down. There’s a (dare I say, literary) essay which almost gets at this idea. It says when asked what an eshay is, an Australian might rightly answer, “You know, you see them on trains.” But is that something just that the thing is good? Um, no, I say. That’s a value judgement, not a genre. In my piece, I argue that while fantasy fiction works are driven by the presentation of realities far removed from a reader’s waking experience, literary fiction works are driven by experimentation with form and the prose within it. A literary work doesn’t need to be good at this – this just needs to be the most important thing about it, above and beyond the characters, the plot, the worldbuilding. And literary fantasy? Now it seems much easier to define. If your experimentation with form and prose supports your efforts at creating a magical reality, now you’re working in the hybrid genre. Whether or not you’re good at it. To celebrate the BFS Journal’s winter issue, I'm joining Avery-Claire Galloway (fiction editor at The Peacock's Feet), Dr Joyce McPherson (biographer of George MacDonald) and Amanda Coleman White (Ink Sweat and Tears feature) for an online launch event . Apologies to my Brisbane friends, it will be at 4am on December 11 for us – but for those across the pond I would be delighted to see you register. Word Count: 510

By Aoife Hilton

•

November 11, 2024

This month, The Braddyton is hosting our first and probably only open mic. Events like these can kickstart an artist’s love of performing, building their lonely creative process into a collaborative one. It did for me. That’s why I appreciate other Brisbane open mic events like Ruckus and Echoes at the Cave Inn. Unfortunately, organisers don’t often post advice on how performers can deliver effective content warnings before they speak about something potentially re-traumatising. A performer with experience in delivering content warnings might be able to anyway, but for someone just starting out those thoughts can get jumbled up in the regular jitters of speaking into a microphone. The result is, in my view, catastrophic. A performer usually creates art on a topic like this for catharsis or connection, but their catharsis might cost an attendee a panic attack, a relapse, a waking nightmare – and connection becomes impossible. To succeed in catharsis without causing pain, and making a true connection with an audience member, I believe performers must deliver effective content warnings. These are not crowd-wide platitudes, off-hand, half-baked asides. They are essential for ensuring those who cannot connect with you right now have the opportunity to decline on their own terms; and equally, those who can have the opportunity to choose to. Before hosting a curated event, I let each performer know that we expect Braddyton attendees be given this opportunity to choose. Here is a more full guide for your reference: 1. What to flag When looking at your own work, it can be hard to see what in it might affect people in different ways – especially if it was cathartic for you to create. Take a step back and analyse with a bit of coldness what subjects it actually broaches. It doesn’t matter how lightly, how nuanced, how true to your experiences, even how funny it is. If it covers suicide (+ideation), abuse, gendered violence, sexual violence or harrassment, self-harm (including skin-picking), disordered eating, grief and death, or drowning, it definitely needs a warning. If not, a good test would be: ‘Have I ever not wanted to hear about this for a bad reaction in the past?’, ‘Would I have appreciated a warning about this at some point?’ or ‘Would anyone I know?’ 2. What not to flag I want to reiterate here that a content warning is not an off-hand crowd-pleasing aside. It actually informs how some audience members will take in your piece, even if you don’t see anyone leaving. In the past, I’ve seen performers follow an act delivered with a content warning by standing up and delivering their own as a joke. Think: ‘The last act might have involved a lot of insect-talk, but content warning, mine involves a cute cat’. I’m not saying these comments are made with malice – when you’ve seen a formula in previous acts and you can’t follow it, you tend to try to make up that you do. If you want to sing a song about a cute cat and there is nothing to warn anyone of, that can also be true. You are allowed to not say anything, even if you follow acts which discuss difficult topics with proper content warnings. I can assure you, the joking content warning route is only hurtful. It makes a mockery of a process designed to help people feel safe in a creative space, and instantly designates you as an unsafe person as a result. 3. How much time to give those affected Okay, we accept when we need to deliver content warnings and that we shouldn’t make fun of them on the mic. But they can be kind of useless, right? When you’re in a big venue and it will take people two minutes to leave and you’ll be through the piece anyway by that point? Or when waiting will have others watching as those affected run off, red-faced, as if in a walk of shame? Or when people don’t really know where to go, whether they will be let back in if they step out, or where the bathrooms are? When you haven’t been affected by a piece in this way, this can all seem very trifling. But in the moment, if you have something like PTSD, these things make you feel like there is no escape from the horror you once experienced coming back again. My advice is to familiarise yourself with the venue so you can direct people to the bathroom, to a second room in the venue like a rooftop bar if they have one, and reassure those who choose to go outside that they will be let back in. This might sound a bit weird, but it is okay to waffle a little bit. It will give affected people time to leave if they choose to, without the awkward silence. Here’s a little script if you need one: "This piece references [subject]. If you just don't want to hear about that right now, feel free to take a piss, go for a smoke, grab some air, or pop in to the main bar. [Front door staff member] will let you in afterwards. It will take [however many minutes]. Here it is." Word Count: 863

All rights reserved | Aoife Hilton | Website by Rhys Dyson